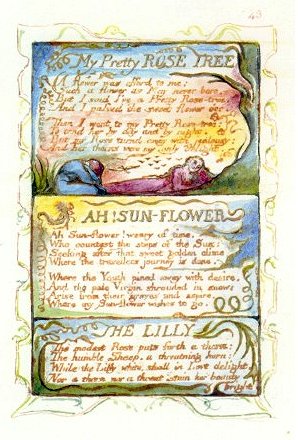

"The modest Rose puts forth a thorn:

The humble Sheep, a threatening horn:

While the Lilly White, shall in Love delight,

Nor a thorn nor a threat stain her beauty bright."

-Blake-

Today I shall speak of Lili, lovely Polish Lili, who emigrated to America from Israel, and whose accent is landless, and whose words are a balm. Lili has silvering, straw blonde hair--moonlight in a hayloft--and the consistency of her hair is also straw-like: no liquid metaphors for our Lili, no waterfalls or rolling rivers, no, nor any similes cut from the seamstress's cloth, no satins or silks or such-like; Lili's hair is uneven as wild-meadow grasses and Lili is beautiful as the jagged-hem of the dawn. She is round, Lili is, round and complete, and she wears shoes the color of grapes wanting-pressing, and her lips are lacquered red as Syrah. And her lips are crenelated from fulsome years on three continents, and Lili is all the prettier for it, and when she smiles she reveals teeth parted as the red-sea, and you cannot help but smile back in return.

Lili had brought Orwell to the coffee shop. Down and Out in Paris and London. It was Orwell who introduced us, for Orwell is a good friend of my father's, and I make a point of being friendly to my father's good friends. Then Lili asked to be introduced to my own companion, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, a lady who doesn't socialize round here very often, and with whom even I am only seven-pages acquainted. Sedgwick is rather awkward lass to introduce to ladies at coffee shops; Orwell conforms to coffee-shop banter quite nicely--he'll talk politics, or regale one with a stirring travel-yarn or two--but Sedgwick, well, so far she's only wanted to debate the semantics of "gender" (or "The Epistemology of the Closet" as she puts it), and that's not the sort of topic one brings up in casual conversation. Then again, I was halfway relieved that it was only Sedgwick and not Benjamin Hale who was with me that hour, for Hale had been with me earlier in the afternoon, and he had brought along his articulate, taboo-breaking chimp, Bruno, and as Bruno had, when last I saw him, been running amok, hairless and bloody, biting his way through a buffet of human limbs on his way to a sorely unenviable freedom, I was rather glad that he was at that point sound-asleep out of view. (I suppose I should note, for the record, that it is my professors who have partnered me up with these companions; not that I have not found the company interesting or educational, mind you, only that it is not company of my own, unobligated, free-choosing).

Lili and I discussed literature, and the unpredictability of life-circumstances, and the difficulty of finding eligible bachelors among, as she put it, the "petite bourgeoisie" of the local area (I think she broached this topic to offer an explanation for my singleness, as she herself had been married for several decades). I asked her if she was happy, and she said no, not exactly. Happiness is a complicated thing. That was her thought on the matter. I agreed, but averred that at least there, in that present moment, in the coffee shop, I was happy, and she added her own hearty assent. It is true, said Lili: it is hard to be sad in a coffee-shop.

Yesterday, in another coffee-shop, I met a chap called A______ from Albania. A_______ said I must come from the mountains, given my accent. This is an odd thing to say, made all the odder by the fact that A______ is the second person to comment thus in the last two weeks. A______ was with a friend whose name I cannot recall, a friend who had recently married a Russian lady he met on a cruise. A______ said the Russian had attracted his friend's attention on the basis of her ability to cut the heads off of fish, a story I very much wanted to believe, but of course it was entirely untrue: A______, A______'s friend, and I said not one non-fictional word to one another for a full forty-five minutes, preferring to weave elaborate and comic tales about our homelands and upbringings than to approach anything approximating the truth. Yet when A______'s friend left, A______ started speaking sincerely of melancholies and heartbreaks and recently failed relationships. A_______ told me that the thing which hurt most was that he had been really serious about the most recent relationship, and had gone so far as to purchase an engagement ring (for this is what the lady had said she wanted). He asked me why it was only after this point that she had begun to show discontent. I did not know. I wish I were wise; I wish I had answers for questions such as this one, but I do not. All I can offer my fellow man is an ear; I am all confessional and no counsel. The lady had left and he had bought a dog. "I am not a dog-person," A______ said, "but I have bought one. A pug of all things." The pug is uncomplicated. The pug does not cry, and the pug does not leave.

Lili and A______. I wonder if it is quite right for me to tell these stories. I wonder if it is a breach of some unspoken coffee-shop confidentiality. I have discussed with friends, before now, the idea of writing a book of my conversations with strangers, for I have found the very best of humanity in such conversations. And yet, even here, in the vast anonymity of a blog that gets seldom more than five hits a day, I find myself shying away from sharing the full depths of these dialogues. Aught I record these meetings only in pages unseen? Must I be as one led by Schiller's hierophant, brought before the veiled image at Sais, glimpsing beneath the "airy gauze" and never being able to speak of it after? To see beauty is to wish to broadcast beauty; to observe good is to wish to proclaim good, to discover truth is to wish to uncover truth. Yet my conscience advises I remain silent, even though I am under no articulated injunction to do so. A confessional. Is this what I am? Is this my place and my purpose? I go to the coffee shops, for when I go to them the stories come to me, and I love the stories, for the stories are of my fellow man; the stories are of what is best in my fellow man; the stories are of what is most honest in my fellow man. And through the stories I come to love my fellow man. Yet where I love, I cannot help but wish to sing my love. Love is the least selfish, the most giving thing of all things in the universe. But if I am a confessional, how can I, in good conscience, sing my love? How can I share it? Oh world! One day man will be unafraid to expose the best of himself to the whole world; one day he will not look upon his finest virtues as weaknesses requiring hiding, as things utterable only to strangers.

No comments:

Post a Comment